A Guide to GraphQL Schema Federation, Part 1

Getting Started

This is the first part in a series of guides on schema federation. In this part, we will introduce schema federation, walk through a few different services that we will use in future posts, and go over some details that illustrate how the system works.

The examples in this series use a package which I currently maintain but the explanations should be able to fit any federated GraphQL gateway.

What is schema federation?

Schema federation is an approach for consolidating many GraphQL APIs services into one. This is helpful for companies with multiple teams that contribute to different portions of a single API or to enforce domain boundaries with separate services.

The defining characteristic of schema federation (when compared to other techniques like schema delegation) is that we are allowed to spread the definition of a particular type across service boundaries where it makes sense. Allowing types to be defined this way not only gives us more flexibility, it also provides the gateway enough information to handle queries that span between multiple services without forcing us to write a bunch of logic by hand. We’ll go into more detail on that later.

What we’re building

Throughout this series we’ll be building out a platform that allows users to auction off photos of their pets. The rough idea is that we want to allow Users to create Auctions for a specific Photo. For now, any User is allowed to create a Bid on a particular Auction. Each Photo is of a specific Pet that is owned by a particular User:

enum Species {

Dog

Cat

}

type Pet {

name: String!

id: ID!

species: Species

breed: String!

owner: User!

photos: [Photo!]!

}

type Photo {

id: ID!

pet: Pet!

url: String!

}

type User {

id: ID!

username: String!

auctionHistory: [Auction]

favoritePhoto: Photo

photoGallery: [Photo]

}

type Auction {

id: ID!

name: String!

photo: Photo

offers: [Bid]

highestOffer: Bid

}

type Bid {

user: User!

amount: Int!

}

type Query {

allAuctions: [Auction!]!

}For illustrative purposes, we’re going to assume that we have a good reason for this application to be distributed across different services and start from there. Each service will maintain its own GraphQL API and act as the source of truth for a single domain. In this example, we’ll start off with our application split in two services. One of them will be responsible for the pet data and the other will focus on the auction infrastructure.

Auction Service Schema:

type User {

id: ID!

username: String!

auctionHistory: [Auction]

}

type Auction {

id: ID!

name: String!

photo: Photo!

offers: [Bid]

highestOffer: Bid

}

type Bid {

user: User!

amount: Int!

}

type Photo {

id: ID!

}

type Query {

allAuctions: [Auction!]!

}Pet Service Schema:

enum Species {

Dog

Cat

}

type Pet {

name: String!

id: ID!

species: Species

breed: String!

owner: User!

photos: [Photo!]!

}

type Photo {

id: ID!

pet: Pet!

url: String!

}

type User {

id: ID!

favoritePhoto: Photo

photoGallery: [Photo]

}Since each of these services are independent APIs, we don’t yet have a single entry point that can access all of the available data. Pulling this off in our distributed setup implies that two services need to be merged in a way that allows queries to retrieve information from each service. This merging happens in a third service referred to as the “gateway”.

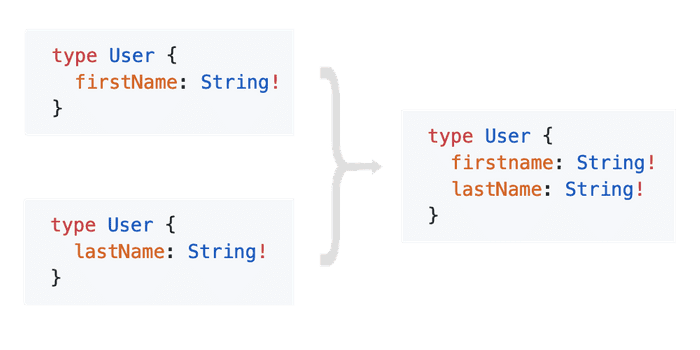

It’s worth highlighting that each service defines a User type. Notice that these two definitions of User have different fields belonging to separate domains. As I mentioned earlier, this sharing of types is what makes schema federation work. Those types that are split between services are known as “boundary types” and the other types that are owned by only one service are called “domain types”. In our example, User and Photo are boundary types, the rest are domain types.

Let’s run our services

For this series we’ll be writing our services in node using the graphql-tools module since that’s what a large portion of the GraphQL community uses. To start, clone this git repository and take a moment to examine its contents.

git clone https://github.com/alecaivazis/schema-federation-demoYou shouldn’t find anything too surprising. All that really matters in there is two scripts: photoService.js and auctionService.js. Running these will start the services we will be interacting with throughout the series. If you look closely, you’ll see that each service defines the corresponding API outlined above with one minor addition: there is an extra interface called Node.

The Node interface

The only requirement that schema federation imposes on a service is that it must satisfy the Relay Global Object Identification Specification. This sound a lot more intimidating than it really is. Basically each service must have a Node interface that looks like this:

interface Node {

id: ID!

}This id field must be globally unique and be usable as an identifier to retrieve that specific record from a field on the root of the service’s API:

type Query {

node(id: ID!): Node

}For reasons that will become clear later, each boundary type must implement Node for schema federation to work.

Our first query

Before we continue, start the two services as described in the demo’s README.

All we need now is a federated gateway. For this series we’ll use nautilus/gateway which is a standalone service that’s designed to fill this role. The quickest way to get going is to download the latest binary from the release page and run it in your terminal:

gateway start --services http://localhost:3000,http://localhost:3001You should now see a message with the gateway’s address. If you navigate there in your favorite browser you’ll see an interface where you can play with the API.

Let’s start off with something simple. Copy this query into the playground and click send:

{

allAuctions {

photo {

url

}

}

}If everything is working you should see a list of every auction in our sample data and the url for each photo. If you take a look at the way our api is broken up, you’ll notice that Query.allAuctions and Photo.url are defined in two different services. In order to resolve this query, the gateway had to first look up each auction in the auction service and then the url for each photo in the photo service.

How does this work?

This section (up until “What Could Go Wrong”) covers the internals of the gateway a little more. It is not required to understand in order to use the gateway, but I felt it was important to cover. Feel free to skip ahead if that doesn’t interest you.

We haven’t had to do very much to allow the gateway to stitch our services together. We just spread the definitions of a few types across our two services and the gateway took over from there. Let’s explore how that happens.

Merging the APIs

When the gateway starts up, the first thing it does is form a single schema that represents the consolidated API of our platform. It begins by introspecting each service to understand what is defined in that service’s api. It then steps through each definition from each service and merges any object types together. Along the way, it keeps track of which services define which fields.

As of Jan 29, 2019, the nautilus gateway only allows definitions for object types to be spread across services. It does allow for the enums, scalars, interfaces, and directives to appear in multiple services so long as their definitions are consistent. The gateway does not allow for input types or unions to be defined in multiple places. If you can think of a reasonable way to do so, please open a ticket on GitHub.

Resolving a Query

We are now ready to resolve queries!

The query resolution process roughly splits into two different parts: planning and execution. For now, let’s just pretend that these two steps happen on every request. We’ll see in a later post that we can split these 2 steps up for improved performance.

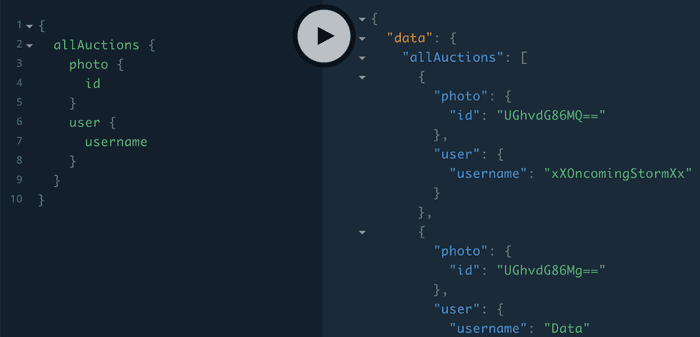

For this discussion, consider a slightly more complicated version of the previous query:

{

allAuctions {

photo {

url

}

user {

username

}

}

}Remember that Query.allAuctions, User.username, and Auction.photo are all defined in the auction service, whereas Photo.url is defined in the photo service.

Planning

When a schema has been distributed across different services, a simple query like this can require going to multiple APIs and asking for different bits of information. Most of the time, these requests have to be resolved in a particular order to look up specific information.

This particular request, for example, has to be broken into two stages. The first has to look up information for each auction by sending the following query to the auction service:

{

allAuctions {

photo {

id

}

user {

username

}

}

}If you look closely at this query, you’ll notice that we requested the id field of the photos even though the user did not explicitly ask for it. By adding this field, the response from the service will contain all of the information that we’ll need later the execution phase. We have to remember that we added this and remove it later from the payload we send to the user.

We now have to add a second step to our plan. This next step has to take the id of the photo that we get from each auction and look up the information for that specific record at the photo service. This is the reason that we require all boundary types implement the Node interface. The gateway must be able to ask for an id to cross over the service boundary.

In order to get the remaining photo information, the gateway has to perform a an additional query for each photo we encounter:

node(id: $id) {

... on Photo {

url

}

}The final result of the planning process is a collection of steps that form a dependency graph of network requests that have to be fired to look up the information the client asked for.

Execution

Once a plan has been generated, the only thing that’s left for the gateway to do is walk down the graph of network requests and construct the response. To understand how this works, consider the response from the auction service if you send the query from the first step:

As you can see we have many different auctions in our sample data. To piece together the final response for the user, we have to grab the id that we added during the planning phase and look up the rest of the information for each auction. This requires sending a copy of the query that we showed in the second step of the plan with the id variable set to match the response we got back from the service.

Once we have the necessary information for each auction, we are done evaluating the query and can send the response to the user.

What could go wrong?

While this approach has many benefits, like any piece of technology there are some things that we need to be aware of.

As with any GraphQL gateway, the number of network requests that can be created by a poorly implemented gateway can cause serious performance bottlenecks at a very small scale. A deeply nested query that cross boundaries a few times can create an avalanche of requests from your gateway. Luckily, this problem has gotten a lot of attention in the GraphQL community and has known work arounds depending on the particular tools you are working with.

Schema federation also has an extra step on top of a traditional GraphQL execution model. The generating of a query plan can get expensive for large queries and should not be done on every request like we previously described. While this also has a known work around, it’s out of scope for this post and will be covered in a later guide.

There is also an entire class of issues that can arise when merging schemas that is not present in the centralized case. While the specifics may vary, the overall situation is the same: it’s possible to form queries or get responses from the API that are inconsistent. For example, two services can have scalars of the same name (DateTime for example) but a different serialization formats. Or, the client could use a directive on a field from a service that does not understand the directive. These issues are not unique to schema federation and are byproducts of splitting the api across multiple services.

Luckily, most of these have workarounds that alleviate their impact. You should consider the details of how a gateway handles each of these problems when deciding on which to use.

Conclusion

In this post, we introduced the project we will be building throughout this series. We then wrote our first query together that was powered by a federated schema! Afterwards, we took a little detour to explore how the gateway is able to do its job and covered a few gotchas to look out for when evaluating different federated gateways.

While this example was small, hopefully it’s clear that this model scales to much larger situations. By splitting our types across services, schema federation ensures that as backend evolves, the gateway is able to accommodate changes in domain boundaries without any intervention on our parts.

That’s it for now. Thanks for reading! If you have any thoughts, please let me know in the comments or reach out on twitter.

If you’re interested in continuing down this rabbit hole with me, you can continue on to the next post in the series where we add a simple authorization system to our platform. If this is where we part ways, I hope you have a nice rest of your day.